- Home

- Yaruta-Young, Susan

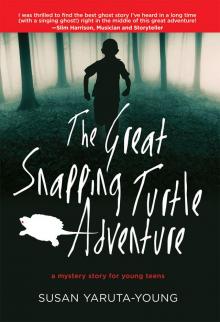

The Great Snapping Turtle Adventure Page 2

The Great Snapping Turtle Adventure Read online

Page 2

“Sell it!”

“Cook it!”

“Charge six dollars or more,” said Max. “Think of it, Charles, six dollars worth of penny candy!”

“But,” said Fred, slowly and carefully, “it’s a lady turtle with eggs to lay.”

“So?” said Charles.

“So, think about it,” said Max. “We could go into the turtle hatching business. Feed those little snappers up big and strong and instead of selling their mamma and making six bucks, we might be able to sell the whole litter or flock or batch or whatever you call a family of turtles. If she had ten eggs, think about that! Ten times six! Sixty dollars!”

“Back to the famous sixty dollar mark,” said Charles.

“Well, guys, I don’t know about all this,” Fred said. “I wasn’t thinking about starting you up in the turtle business. I was thinking more on the lines of letting this poor mother turtle go free. Now that Mrs. Harriston has gone on to Easton, we could let the turtle go about her business of laying eggs wherever she thinks best.”

“Oh, come on, Fred, that would be stupid. There’s really no place for her to lay them on this road. Can’t we just keep her with us? There are so many wonderful places at home where baby turtles could live,” said Charles.

“If you’re thinking about my garden, forget it!” said Fred.

“We could take it over to Turkey Legs Toni’s house,” said Charles. Turkey Legs was their big brother Ralph’s girlfriend. “That pond of hers would be a perfect place for a turtle.”

“Yeah, perfect,” said Max. He was still thinking about a possible baby snapping turtle business, though he wouldn’t admit it.

“Ok, we’ll keep the turtle, for now,” said Fred.

“Yeah!”

“But you guys better haul her into the truck and then wet her down with some sea grass. This is going to be some day. Not only will we be crabbing, but we’ll also be offering prenatal support to one very big snapping turtle. Geez!”

“But we love you, Fred!” said Charles.

“And you did say that this trip was going to be an adventure!” added Max.

CHAPTER 3

ELLIOTT ISLAND HAD A QUIET, “everybody’s gone on vacation” look about it. Hardly any cars on the main road. Instead of screeching brakes, there were dog yawns and tail waggings as the local, four-footed security systems patrolled the gravel and oyster shell lanes. There was so little traffic that Fred had to frequently steer the truck around one of those hairy “guards” as they slept, nose-to-paws in the middle of the road.

Charles, Max, and Fred passed by bright, white-washed houses and rusting trailers, weathered homes that looked like over-sized doll houses, and big rambling colonial mansions with fancy gingerbread trim around the eaves of wrap-around porches. Tangles of brilliant wild and cultivated flowers laced between the pickets of old wooden fences and grew up through crab-trap fence posts.

There was one church in town. A small, white-shingled building. It had a bell tower on top, and a new bronze plaque that stated it was Methodist and had been built in the late 1800s. Beside it, a small graveyard overflowed with old tombstones and raised graves.

“What are they?” asked Charles, pointing to a grave that resembled a stone box. It was placed half way into the sandy soil and was surrounded by carefully trimmed, wiry grass.

“Here on the Shore, some people choose raised graves. This land is below flood level. To keep caskets from swimming away, some families build above-ground stone graves with stone walls. That’s so there’s no way a casket will float away come a bad storm,” said Fred.

“Ugh,” sighed Charles, his imagination showing him more than he wished.

Fred stopped the truck, pulling over onto the grassy shoulder near the graveyard. “Come on, let’s take a quick tour,” he said, getting out. “Down here on the Shore, families sometimes put interesting messages on the gravestones. Some of these graves are very old.”

The boys jumped out. They couldn’t imagine why a graveyard would be a particularly interesting place, but if Fred wanted to take a tour, ok.

They scattered around the cemetery. And soon, almost like seekers at an Easter egg hunt, they began to call out to each other. “Hey, come here and see this one: ‘For James, who was lost at sea during the hurricane of ’09.’ Wow!”

“Over here, poor family. Lost three children all within a couple of days.”

“‘For our little lamb who never gave us one bleating moment!’”

“Or this one: ‘Kings and Queens may be favored in some lands

But here where the sea takes over the marsh

A waterman’s life is our royal pleasure

Noble was he who sought the fleeting crab

The wise striped bass and the hidden oyster

Thank God to have lived

Where the air is salty

And never to have traveled far

From this Eastern Shore’”

The old stones were filled with folksy messages and dates from many years past. It was almost like reading an old newspaper from another time. Pictures were engraved on the monument stones: lambs, roses, ships at sea, and even the wildlife creatures that roamed the land and scurried through the waters. Wild Canada geese fanned across the granite skies, the heron balanced on one leg, the deer stood by a row of pines, while crabs and fish stared out from their worlds of stone.

After about fifteen minutes, it was Fred who was first to signal time to go. “I mean, if we want to catch any crabs, we better be leaving here,” he said as he made his way to the truck.

“But this is so wild, scary and different,” said Max, slowly ambling back to the truck. “Look!” he suddenly called out.

“What?” answered Fred and Charles at once.

“This gravestone! The name is Hattie Harriston!”

“What!” said Fred and Charles together. They both hurried to Max.

“No death date. Just: ‘Born January 6, 1900,’” said Fred, looking at the stone.

“But the stone is sunk so far down, if there was a death date it would be hidden. I mean, it does say ‘Died,’ but you can’t see a date because of the earth.”

“But how can there be a death date when she isn’t dead?” asked Fred. “Come on, you guys, that lady on the road holding onto a snapper was no ghost. You must have been breathing in too much marsh air, and the salt is clogging up your brain cells, making you think silly impossible things.”

“Still, it’s pretty strange to meet a lady and then a bit later to see her gravestone, don’t you think?” said Max.

“On the Shore anything is possible,” said Fred. “Come on, let’s look for the best place to crab. Stop thinking about ghosts. Granted, the Shore is filled with all kinds of spooky tales of strange sights, but let’s put our minds on other things like crabs and keeping a lady snapper happy. We can think about ghosts and strange Shore tales tonight when it’s quiet and cool.”

“Tonight my mind is going to be filled with the names on these gravestones: Harriston, Truitt, Dickerson, Webster, Brinsfield, Spence. Over and over like sheep jumping fences. I can see them now!” moaned Charles.

“Geez, I’m glad I have the less creative mind,” said Max.

CHAPTER 4

ITHINK WE’RE LOST!” said Fred, braking beside a pile of oyster shells that towered as high as the cab of the truck.

“How can we be lost on such a small island?” asked Max.

“I think sometimes I could get lost in the bathtub if it weren’t for the soap dish attached to the wall helping me to keep my bearings,” said Fred with a laugh. “No, I just can’t seem to remember where the turnoff is for a small public beach I know of here. I don’t want to go invading someone’s privacy by venturing onto a private beach by mistake. We better stop and get some information.”

“Where?” asked Charles.

“At the post office. They should know,” said Fred. He turned the truck off.

“Where did you see a P.O.?”

&

nbsp; “Here,” said Fred, getting out.

“Here?”

“Here.”

“Where?”

“There,” said Fred, pointing to a small wooden building no bigger than a large tool shed. From out of a window, equipped with prison-black bars, the great square face of the postmaster peered out at them.

To Max and Charles, he looked as big as the entire building…as if he were wearing the post office as clothes.

When Fred and the boys walked up to the building, the postmaster said, “Mornin’,” in a voice as slow and round as a bubblegum bubble.

“Mornin’,” said Fred. “We’re looking for the State Park. I wonder if you could help us.”

“Hmmmmmm,” said the postmaster.

While he was slowly answering Fred’s question, Max and Charles circled the post office. Looking in all the little windows, they saw various parts of the big man.

“He’s like Alice when she grew too big for the White Rabbit’s house,” whispered Charles.

“Enormous!” Max whispered back.

“State Park, hmmmmm,” said the postmaster. His voice popped through the little building as his body bounced up and down. His weight moved from his toes to his heels, back and forth, like a great mustached balloon trying to break free from its cord.

It was hot in the little post office. The postmaster’s face burned red. He rubbed it with his great paw of a hand. The skin of his brow rolled to the fat of his toad cheeks. His sausage nose pushed to his red jelly bean lips, over to his cauliflower ears, then back again to the layers of his neck.

“State Park…well, we do have a piece of waterfront, over past White’s. That’s the place with the picket fence you passed on your way into town. You be ok to crab there. Nobody say anything to you and if they do, all you have to say is Ham at the P.O. told you it was ok. Got that?”

“Yes sir,” said Fred.

“Say, where you folks from, anyway?” Ham had detected a foreign accent. No one born on the east side of the Chesapeake Bay talked as quickly as Fred. Words were something akin to the finest, coldest ice cream—to be carefully scooped out and left on the air, leaving the fine smoky-cold impression of sound. One born on the Eastern Shore of Maryland never hurried a sentence to its end. Instead, they let it develop over time.

“We’re from northern Baltimore County, about 2½ hours west of here,” said Fred.

“That so,” said Ham. “I got to Baltimore once. It was ’bout twenty years ago. Some big city. Pretty lights and all, but I got so lost with all those high-rise skyscraping buildings and no pine trees or barn roofs to use as landmarks. I was afraid I’d never find my way back home!” He rubbed his face again.

“Lots of people there,” Ham finally sighed.

“Sure are,” agreed Fred.

“Folks around here go up to Baltimore sometimes when the Oriole Birds is winning at baseball,” said Ham.

“Go O’s!” shouted Charles, in support of his favorite baseball team.

“How many people live here on the island?” asked Fred.

“Oh, we’re growing pretty crowded lately, after a slump when it seemed like all the young folk wanted to head for the mainland soon as they could walk. Guess we’re up to around 50 or more now. Pretty stable community. Most of our folks are water people. They spend their whole lives reaching down deep into the oyster beds or spreading out a trot line for the blue fins when the month don’t have a letter ‘r’ in it.”

“Letter ‘r’ months?” asked Max. He was back from his tour around the tiny building.

“A good waterman only harvests oysters in a month with an ‘r’,” explained Fred.

“That’s right. Our boys respect the oyster. They pitch out after ’em come September and work their tongs ’til April. From April to September, it’s time to let those ol’ oysters sleep in their beds quiet like. Time to pick up the nets an’ some good chicken renderin’s as bait, an’ go a’scamperin’ after those blue fins.”

“Blue fins?” asked Max.

“Blue fin crabs. A beautiful swimmer he be. Ever seem ’em with their lady friends?”

“No,” said Max and Charles together.

“Why, a male crab will hold his lady in his lovin’ fins and whisk her away on top of the water. You can see them from a far bit away. Just a little scratching of fin on the silver surface when the Bay is calm as satin. I tell you, it’s a beautiful sight! An’ then, should he see you! Down they go, deep into the shade of the sea grass and quiet.” Ham gave a soft whistle out of the triangular break in his front teeth. “Here on the island, we folks have a lot of respect for the ol’ Jimmie, that’s what we call a male crab. We respect his lady friends, too.” Ham paused to wipe his face and then continued. “A crab is a dandy dancer. When I was a boy, long time ago now, I was once out walkin’ with a net, lookin’ for softie crabs, when up I came on a most amazing sight. In all my years, I never did see the repeat of it! There were twelve crabs in a circle. It was like they was havin’ a ring-around-the-rosy dance. I just stood back an’ admired ’em. It was a true miracle, an’ what’s more, that miracle continued, ’cause even though I were a cracker jack crab netter, usin’ a long-handled net like it were a tropical fish scoop, do you know something? When I tried to scoop up a few of those dancin’ beauties, my net came up filled with mud and sea grass but no crabs. The dancin’ dozen had all gotten away.” He laughed at the memory and his wide head waddled back and forth.

“A dozen in a circle dancing!” exclaimed Fred. “That must have been something to see!”

“I never forgot it. I can tell you this: it’s been a picture snapped in my brain all these years.” Ham shook his head some more.

“Tell him what we have in the back of our truck, Fred,” said Max.

“Whatcha got?” Ham pushed his face up closer to the bars and peered at the truck.

“A giant-size snapping turtle!” yelled Charles before Fred had a chance to respond.

“That so. Where’d you come upon him?”

“There was a little old lady standing in the middle of the road as we were coming down here. She was holding him out by the tail, like he weighed nothing.”

“Did she say who she was?” asked Ham.

“Hattie Harriston,” answered Fred.

“Hattie Harriston? Nope, weren’t her, I don’t think,” said Ham. He paused a moment, then continued, as if speaking to himself. “But here at the End of the World, I guess nothing’s too strange. An’ were it Hattie Harriston you saw, then the man with the limo would have been her fancy pants son. He thinks himself something too good for Elliott Island people. He forgets where he were born an’ raised. But Hattie would know ’bout snappers an’ most anything else there were to know about the Shore.” Ham stopped, then turned to Fred. “So she gave you a snapper ’cause her son wouldn’t let her put it in the car?”

“That’s right,” said Fred.

“An’ the turtle is a big one?”

“Yep, and Mrs. Harriston said it looked like it was ready to lay eggs,” said Fred.

“If Mrs. Hattie Harriston ever said anything, I’d believe her. She used to talk to elves, you know.”

“Elves!” said Fred and the boys together.

“Yep, elves. At night. She’d tell me how they helped her with the gardening. Told her when to put the little plants in the ground come spring. An’ you know, her garden was always the finest. Biggest strawberries on the whole island. Strawberries as big as peaches…take you four or five bites just to finish one off.”

“Wow!” said the boys.

“An’ her corn! Sweetest I ever tasted. Melt in your mouth. She was a farmer with a real touch an’ she had most folk down this way believin’ she did have elves helpin’ her out. Most folks exceptin’ her son, that is. He was convinced she’d gone nuts. Had her committed to a home up in Cambridge. A real shame it were, too. It was the undoing of her. She was a healthy spunky ol’ gal ’til that happened. We all here on the island feared it would put

an end to her, an’…” Ham stopped and wouldn’t go on.

“Oh no,” sighed Fred.

“Well, maybe I heard it all wrong. Gossip gets sort of mixed up with fishing lines down here, an’ what you sometimes hear ain’t the end-all of it. Maybe she’s been let out. Hope so. If Hattie told you she were givin’ you a lady snapper, then believe it.”

“Do you think the turtle will be ok today while we crab?” Fred asked, trying to return to crabs and things that were easier to understand.

“Turtle should be fine as long as you keep her wet. Throw some seaweed on her an’ keep a little bit of the basket tied in the water…not deep, but just so the water can keep slappin’ up against her, keepin’ her cool. She should be fine then.”

Ham gave Fred directions to the public beach again. He wished them well. “An’ if anyone gives you any mouth, just tell ’em Ham at the P.O. told you it was ok. Tell ’em you’re my guest an’ the guest of Mrs. Hattie Harriston. That should shock ’em so much they’ll leave you be.”

“But we aren’t really Hattie Harriston’s guests,” said Max.

“Oh, yes you are. If Hattie Harriston showed herself to you an’ let you pass down the road, then you’re her guests.” Ham shook his head so hard the sweat sprayed off of his face like salty rain. “Good luck, now!”

“See you, Ham!” the boys and Fred called as they went back to the hot truck.

Inside the cab, everyone was quiet for a few moments. Then all three spoke at once.

“This is getting stranger and stranger,” Fred whispered.

“What is this stuff about Mrs. Harriston?” asked Charles.

“Is any of this real? An old woman holding a snapping turtle, a gravestone with her name, and then Ham!” said Max.

“Well, I told you we were out for an adventure,” said Fred.

“And an adventure we’re getting!” ended Max.

“Yeah, kind of an Eastern Shore version of Alice in Wonderland,” added Charles.

CHAPTER 5

The Great Snapping Turtle Adventure

The Great Snapping Turtle Adventure